About a year ago, Purdue engineering professor Andy Whelton launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund his research on what is known as CIPP (Cured in Place Pipe), in part because he had to use some of his own money to keep it going .

“When they cure the materials, they basically pull this damp, wet, chemical-filled sock into the tube. They seal it and then heat it,” Whelton says.

This sock will expand to fill the tube and after a few hours any internal cracks will be covered with a new layer of material. Half of all water pipe repairs in the United States are now done this way. Whelton opens a red picnic cooler that contains pieces of concrete, each wrapped in its own heavy plastic bag.

“I mean you can feel it. It couldn’t get any more difficult, “says Whelton as he taps the hardened material.” And it’s fiberglass with resin in it. And one of the main chemicals they use in this process is called styrene – a well-known human carcinogen. “

Whelton had begun investigating CIPP after receiving multiple calls from people who lived or worked near locations where it was being installed. This styrene creates a strong odor, which is one of the tell-tale signs that something called “trenchless pipe repair” is taking place nearby.

In fact, US and Canadian news contain stories about the smell.

The companies that install CIPP say the smell is from styrene and it dissipates quickly. But Whelton says there was little data to show that was all.

“We care about when they pump that vapor in,” Whelton says. “And the smell gets very, very strong when they pump it into the work area, or there is this white stuff floating around in the air. What’s this? What are the exposures? “

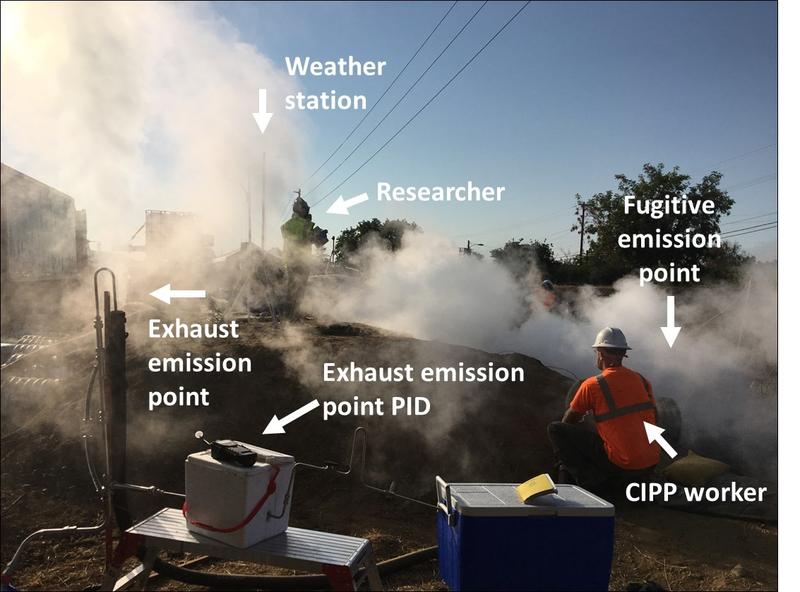

This white cloud also became a focus of research. Whelton and his team visited several sites and placed air quality monitors in and around the chemical clouds to collect emission samples that the professor now definitely says are “not vapor.”

The video, captured by his team at a location on the Purdue University campus, shows workers in orange vests, but no other safety gear, as they walk in and around a cloud flowing from an open manhole.

Whelton also filed requests for public records with several American cities that he knew had used CIPP. Some, like St. Louis and Los Angeles, sent back the data he requested. Others, like Chicago, said they couldn’t abide by it because a private company is doing repairs for the city and is not subject to public records laws.

It was all months ago. When we caught up with Whelton on the eve of his results being published, he was less clear about what his tests were showing.

“Based on what we’ve seen, the steam cured CIPP should no longer be used as it is used today,” says Whelton. “Changes need to be made.”

The paper, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology Letters, shows that there are more than a dozen chemicals in the chemical plumes, which Whelton says include other known carcinogens besides styrene.

But Gerry Münchmeyer, who is now a CIPP advisor and previously served on the board of the National Association of Sewer Service Companies (NASSCO) (the trade group advocating trenchless repair technology), says he has his doubts.

“You know, to be honest, I’ve seen a lot of reports, and many of them were flawed,” says Münchmeyer. “I mean, the industry is testing this all the time and we know exactly what the concentrations are and so on. And the information was absolutely impossible – it couldn’t happen. “

Ironically, both Münchmeyer and Whelton use the same rationale for their arguments – that their data is better.

“I have no problem looking at such problems, but the data must be correct. The data must be correct, “says Münchmeyer.” Otherwise, you will post things that are just another scare tactic that has no basis. If it has a basis, something should be done about it, I agree with you. “

“There were two studies that came to my attention that were published by the industry, but they focused closely on certain chemicals,” says Whelton. “They ignored other problems and did not declare most of them.” So you cannot tell whether the data is valid or representative of anything at all. “

Whelton says his team may have the first reliable information about what is being emitted from CIPP steam-hardened sites. Both according to what he measured and what he saw personally.

“At a construction site that we visited and where we collected a sample of the uncured resin, one of the students helped me and I handled the uncured resin, my nitrile gloves, plastic gloves that had dissolved in about 30 seconds a minute,” he says .

Whelton says he expects a setback from the industry. However, he is confident that the National Institute for Safety and Health at Work (NIOSH) will issue a notice through CIPP once its findings are announced. That would give him a powerful ally in his quest to reform a system that will be very busy in the years to come as most states grapple with the fact that they are letting their roads, bridges and pipes rot.

“One of the reasons I chose civil and environmental engineering was because I wanted to help people,” says Whelton. “And so I’ve tried to lead my professional career – can I help people? Because the workers out there are well-meaning people who are rebuilding the infrastructure for us. And the least we can do is make sure their health is protected. “

Whelton hopes his research will lead industry leaders to come see him so they can work together on solutions – solutions he is already developing in his lab.

By then, he’ll see a Wild West-style landscape with no rules – a problem that he hopefully can fix. And as he says, the first cowboy through the door usually takes the most arrows.

Comments are closed.